Police Widows Attempt to care for Their Own

Police Widows Attempt to Care For Their Own

Police Widows Attempt to Care For Their Own

Newsday (New York) March 5, 1989

By Alexis Jetter

Lana Galapo turned on her television set last October for the first time in two months, and froze in disbelief.

She hadn’t watched television since August, when her husband, Police Officer Joe Galapo, was accidentally shot to death by his partner during an undercover buy-and-bust drug operation in Brooklyn.

But on the night of Oct. 18, she decided to soothe her nerves by watching a romantic movie about the Civil War. Instead, she saw the bloody sidewalk in Washington Heights where Police Officer Michael Buczek had just been gunned down.

“I was just in horror,” Galapo said recently, her hazel eyes troubled as she sat in her kitchen in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. “It was just like they had killed Joe all over again.”

She spent a sleepless night, thinking about Buczek’s young widow, Christina. “I just really felt the horror that this girl was going to go through, the nightmare that was going to start for her,” said Galapo, 30. Three days later, she left her three small children with a relative and drove through a rainstorm to the Buczek wake in New Jersey.

“I didn’t know where the hell I was going,” Galapo said. “But I found it, and when I got there, Chris didn’t want me to leave.”

Nothing attracts more attention in New York than the murder of a police officer. But when the funeral is over, when the cries for retribution are stilled and the publicity dies down, the spouse – if there is one – is often left to pick up the pieces alone.

Galapo and Buczek, however, have joined about 20 other police widows in a new organization that hopes to transform grief into action for the New Yorkers whose police officer spouses have died in the line of duty.

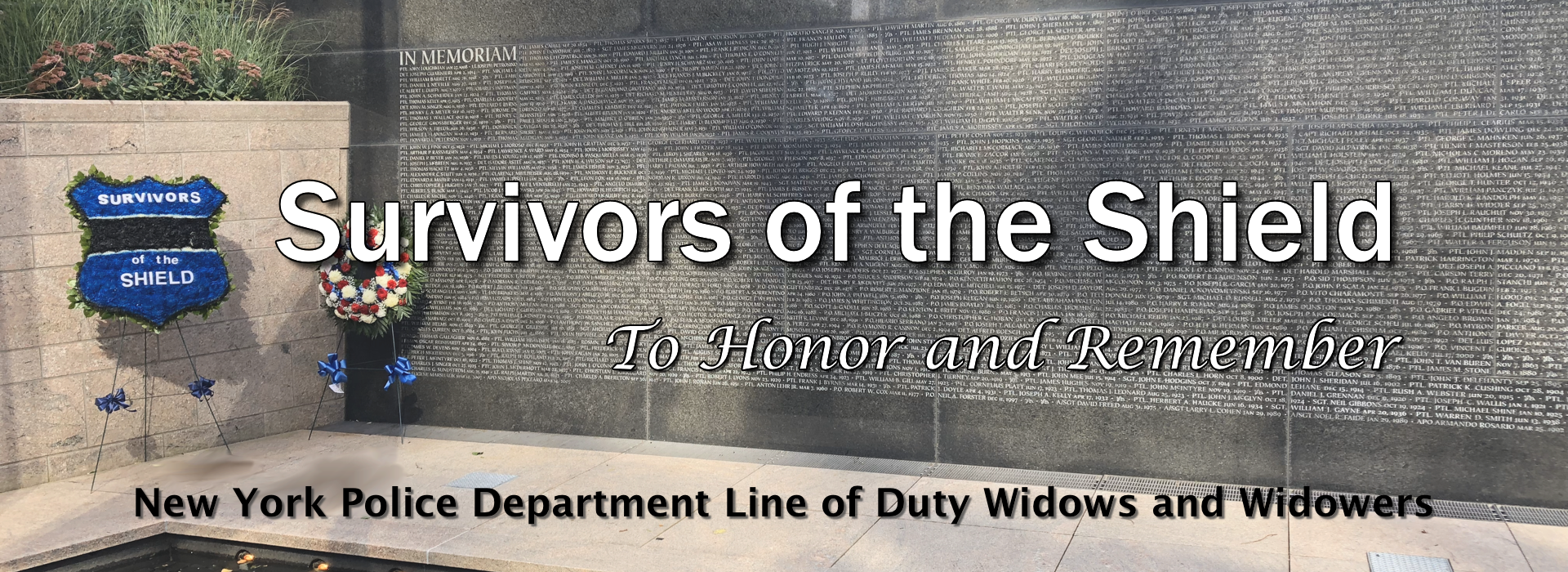

Called “Survivors of the Shield,” the fledgling group plans to dispatch widow “response teams” to the home of a bereaved spouse after a police shooting, lobby for pension reform so that widows, if they remarry, are not forced to forfeit their husbands’ pensions, alert them to be on the lookout for signs of trauma in their children years after the death, and provide a buffer against the loneliness that envelopes their lives after the last bagpipe has sounded.

Although not yet sanctioned by the police department, the group sprang into action Friday, when Police Officer Robert Machate was killed by a Brooklyn gunman. At 7 a.m., Mary Beth Ruotolo, SOS vice president, got a call from Galapo telling her about the shooting. Moments later, Ruotolo called the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association and the employee relations division of the New York City Police Department. She told them the Brooklyn response team, consisting of Galapo and another widow, were ready to talk to the officer’s young wife whenever she felt ready.

SOS members hope that the initial contact will prepare her for – and perhaps spare her from – some of the pain.

“What happened to us was such a shock,” Galapo said. “From Day One, when it happened, we all go through the same thing: We go through the everybody-cares business right down to nobody-comes-around-anymore.”

SOS is not the first organization for police widows. Other local and national organizations lobby for increased pensions and provide grief counseling to police widows. But SOS is one of only a handful of groups across the nation fighting for official, active participation in a drama that has for generations limited women to the role of grieving wife.

The president, Susan McCormick, said the group is seeking official recognition by the Police Department so its response teams are notified immediately after an officer is shot to go with the first officers to tell the family about the death. “So you’re not just some lady by the phone saying, ‘call me if you need me,’ ” she explained.

The idea has drawn support from the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association but mixed reviews from the Police Department. Police officials question the psychological benefits and worry about the logistical problems of widow response teams.

But the women say they can handle the stress, and want to put their particular brand of knowledge to use. They can talk about the jarring pain of hearing about their husbands’ deaths over the radio. Or the days when, despite scores of microphones pressed to their lips, they could not speak at all. Or about forcing doctors to tell and retell the grisly details of their husband’s final moments because, somehow, they must know.

And while they appreciate all that is done for them, many of the younger women say they need more than memorials. They want, through counseling and companionship, to help other widows avoid their scars.

“I don’t want to keep saying how much it hurts,” said Christina Buczek. “I’m in search of a different message to the public.”

There is a blur of blue when a police officer dies. A priest comes to the door with a retinue of cops, most of them strangers, to break the news – even though many women say they had already guessed the worst from sketchy details on television or radio. The police fraternity takes over: Calling the hospital, arranging the funeral, removing guns from the house (because the registered owner is now dead), and keeping reporters at bay.

Denied a private expression of grief by the press, the women say they took some comfort in the rituals provided by their husband’s colleagues, most often men. But the police fraternity, so attuned to action, can be clumsy in grief.

“It’s not like we were neglected by the Police Department,” said Mary Beth Ruotolo, 32, of Dobbs Ferry, whose husband, Officer Thomas Ruotolo, was killed by a parole violator on Valentine’s Day, 1984. “They just don’t know what our needs are.”

Some women found themselves accepting advice they later regretted. Like Susan McCormick, 41, who – on advice from the department – decided against going to the hospital after her husband was fatally shot in the chest by a Bronx gunman. Her last image of Joseph McCormick, an Emergency Services officer, was watching him step out of their house in Carmel on a beautiful September day in 1983.

She did not see him again until three days later, when he was laid out in a casket. Now, McCormick says, she feels cheated. “They think they’re protecting you,” she said. “But I feel a loss from that. Here you see him going off to work, and the next time you see him is in full dress uniform lying in a coffin. There’s an unreality about that.”

Dr. Gregory Fried, deputy chief surgeon for the Police Department, is frequently called to the scene of police shootings. He said he routinely advises family members not to see the officer’s body if it is mutilated.

“I try to talk the wives out of seeing their dead husbands,” he said. “To see someone’s head blown off or hideously swollen will leave them with a horrible image in their minds for the rest of their lives.”

The women of SOS say they want to give the widow support to make her own decision.

Sometimes the team dispatched to notify the widow simply cannot find the words to comfort her. Christina Buczek fondly remembers the young priest who came to tell her that her 24-year-old husband had been killed. But she couldn’t say anything to him – or to anyone else.

Buczek, 24, had already figured out from the evening news that the unnamed police officer slain at West 161st Street and Broadway was her husband. She was frantically calling the 34th Precinct and her sister-in-law when she looked out the kitchen window of her Suffern apartment and saw the officers climbing out of the patrol car. She hung up the phone, and stopped speaking for three days.

It was only when relatives called the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, which then asked Mary Beth Ruotolo to pay a visit, that Buczek found her voice.

“Everyone is watching your every move . . . I think I just withdrew because I didn’t want to believe it,” Buczek said. “But there was a presence there of somebody who knew. There’s just a sense of security there.”

Sometimes, the official police routine is awkward. When Lana Galapo, a Sephardic Jew, opened the door last Aug. 16 to find a priest, she knew it could mean only one thing. “Actually, it’s terrible,” she said. “A priest means bad news to a cop’s wife.”

For Galapo, the embrace of the police fraternity was bittersweet. Officer Galapo’s partner and mentor, Sgt. William Martin, inadvertently shot Galapo in the face when a handcuffed drug suspect jostled Martin’s arm.

“It makes it harder to swallow,” Galapo said softly, her face illuminated by a memorial yortzeit candle. “I don’t hate him. But I don’t know what to make of this whole situation. My whole life went up in smoke in seconds.”

Martin came to the services for Galapo to offer his condolences last August. “Other than ‘I’m sorry,’ there wasn’t much he could say,” Galapo recalled. “He was in a lot of pain that day.”

The two men were close enough that Martin had attended the circumcision ceremony for Galapo’s youngest son, Richard, now 2 years old. “I try and let them not hate or resent anybody,” Galapo said of her children, one of whom still has nightmares about the shooting. “But it doesn’t seem to make any sense to them. From what they see on TV, the good guy always wins.”

Lana Galapo says she feels worst for her children. Recently, she took her three youngsters for a vacation in Pennsylvania, to a hotel they frequented when her husband was alive.

“The kids started to cling to people in the pool,” she said, caressing the shoulder-length locks of her youngest child, Richard. “I had to go over and say: ‘You can’t hang on to this guy all the time. He’s here with his kids.’ “

The men often asked where the children’s father was, she added. “Answer that one without crying. It’s something that tears your life upside down.”

Susan McCormick bristles when she hears people say that she should have been ready for her husband’s death. “The public doesn’t see us as victims,” she said. “Because a lot of people say, ‘Well, that was his job. He was paid to do that. You should have been prepared.’ “

Is it possible for the women to be truly prepared? Their husbands worked in dangerous fields, and in dangerous places. Galapo was an undercover narcotics officer. Buczek worked in drugand violence-ridden Washington Heights. Ruotolo worked in the “Fort Apache” precinct in the south Bronx. McCormick handled hostage situations.

But the daily risk on the job was something most of the women simply put out of their heads. Otherwise, they said, they wouldn’t be able to live. Buczek said she didn’t get a full sense of her husband’s working conditions until a few weeks after he died, when she developed a roll of film he’d left behind. “It was pictures of a murder scene,” she said, grimacing at the memory. “I never realized what they see every single day.”

In September, 1983, Sue McCormick lost her husband. In the following months, she felt like she also lost her family. The couple had married one month after he joined the Police Department, and for 15 years, McCormick said she knew no other life than that of a police officer’s wife.

“You get used to the schedule, you understand the lingo, and you feel part of a world that nobody else understands,” she said, talking over the hum of the refrigerator in her mother’s apartment in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. But after the shooting, McCormick no longer saw her husband’s partner and his wife, and soon lost virtually all contact with the Police Department. “Not only have you lost your husband,” she said. “It’s almost like being drummed out of the corps.”

McCormick and others suspect that seeing widows is too painful a reminder for cops: of their dead friend, and of their own mortality. For McCormick, the new group holds the promise of reviving the police family, but on a new footing: her own.

The group has not yet approached the Police Department with its proposals, but Alice McGillion, deputy commissioner for public information, said she was receptive. “They’ve been through an experience that none of us has,” she said. “They might have some insight into the situation as to why it should be done.”

Fried, who has counseled several police widows since assuming his post in 1981, said he had reservations. “It’s easy to say: ‘I want to help,’ ” said Fried. “But it’s a hard, hard job. I personally don’t think many of them would like to relive a killing . . . They’re going to face flashbacks.”

Some women may not want the shoulder offered by the widows, added a source at the PBA. Several women want nothing to do with police, widows or even New York City after their husbands are killed, and the PBA has lost track of many women who have tried to put the experience behind them.

But the women of SOS feel that, with training, they can provide a valuable service at a critical time.

Groups like SOS can be of enormous assistance in combating the depression that inevitably follows the loss of a spouse, said Phyllis Carpenter, a counselor and police widow from Grand Junction, Colo. She runs support groups for the Concerns of Police Survivors [COPS], a national organization for families of slain police officers. “There certainly is a catharsis, of feeling that you are not alone,” she said.

The idea for SOS came two summers ago, at the annual week-in-the-Catskills vacation provided by the PBA for widows and their children. Originally hosted at the old NYPD camp in Tannersville, the event has been held in recent years at the Concord and other hotels.

“It’s a summer vacation we give to them and their children under 18,” said Edward Haggerty, recording secretary for the PBA. “So they have a diversion.”

The PBA also hosts an annual Christmas party for the families.

The police union welcomes the new group’s efforts.

“Any support that can be given to someone under these tragic circumstances from another person who’s been through a similar trauma could only be helpful,” a PBA spokesperson said

McCormick, who had been attending yearly meetings of COPS, suggested the New York City contingent start its own organization. Ruotolo and another woman, Cathy Murray, agreed.

The group held its first meeting at the 112th Precinct in Forest Hills, Queens, last November, which drew 23 widows. Leaders of the group, who say they would welcome police widowers if they wanted to join, met last week with a psychiatrist to organize training sessions in grief counseling. They hope to begin officially sanctioned operations in coming months.

There are, however, some tricky issues left unresolved. In the event of a non-fatal shooting, for example, should widows appear on the scene?

Lori Gunn thinks so. Gunn’s husband, Police Officer William Gunn, 28, was shot along with Det. Louis Rango on Jan. 20 in Bedford-Stuyvesant. A few weeks ago, Lori Gunn got a call from Lana Galapo.

“At first when she called me, she was afraid,” said Gunn, whose husband is paralyzed and has suffered extensive brain damage. “She didn’t want to scare me” with the specter of widowhood.

It is awkward, Gunn conceded, to find herself socializing with widows. “It’s not the most pleasant thought. But if I have to weigh that against what I get from them . . . ” She paused. “He’s never going to be Billy again. Lana’s way ahead of me, so whatever happens, she’ll help me.”