NYPD Blue: Grief Of Slain Cops’ Kin

Newsday

March 20, 1994

BYLINE: By Vivienne Walt

The pain comes on with a sudden jolt, often beginning at the sound of two small words: “Cop shot.”

Some catch the dreaded phrase while they listen with half an ear to the radio. Others see it scream at them as they stroll past a newsstand, or pick their newspaper off the doormat. But for the widows, parents and children of police officers killed on the job, the effect is usually the same.

“Every time I hear that, I get chills. It’s like living through it all over again,” said Michael McDevitt, whose father, Henry, a detective in the Bronx, was killed when he fell from a high window while chasing robbery suspects in 1977.

“I heard about Sean McDonald in my car on the radio. As soon as I got home I turned on the TV and saw it,” said McDevitt, 32, who was 15 when his father died. “I got a chill through my whole body.”

For Catina Hoban, this week’s shooting was perhaps even more chilling, since it bore a painful similarity to the murder of her son, Christopher. An undercover narcotics officer, Hoban was shot during a buy-and-bust operation on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in 1988. Like McDonald, Hoban was 26 at the time. And like that young rookie, he was shot in the head and chest.

“There was so much I could identify with. I cannot tell you how many phone calls I have had this week,” said Hoban, who has surrounded herself in her Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, home with photographs and other mementos of her son. “They took away my son, but they cannot take away my memories,” she said.

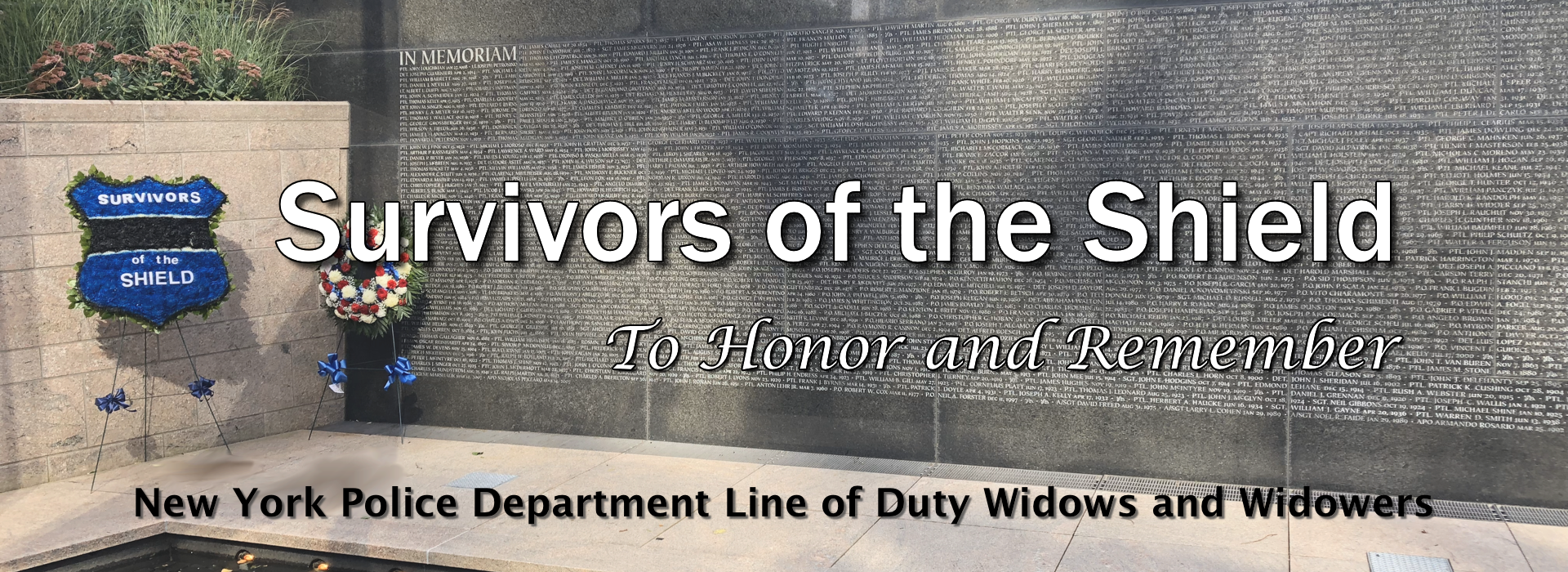

Like many widows of officers who have been killed on duty, Margaret McDevitt keeps close contact with other survivors, writing condolence letters and attending monthly meetings of Survivors of the Shield, an organization formed in 1989 to help pick up the pieces for those left behind.

About 150 active members scattered around New York offer advice on benefits and pensions, organize outings, and attend funeral after funeral. But while they provide crucial emotional support and have successfully lobbied for better benefits for survivors, each death has brought fresh anguish, said McDevitt, who was left to raise five sons alone.

“I’ve gone to several wakes. And I don’t see the fellow laying there in the coffin, I see my own husband’s face,” McDevitt said.

The feelings of grief and loss are almost universal for those in mourning. But the survivors of police officers killed on the job also express other complex emotions, which some say they have spent years in psychotherapy trying to resolve.

“At first it wasn’t anger. I was hurt. But after a while, it turned into anger,” said Michael McDevitt, who has received extensive therapy since his father’s death. “For some people, that anger stays with them, and they blame a color, a race. That’s not right.”

McDevitt, who lives in Massapequa, wanted to “pick up where my father left off,” by becoming an officer. “I wanted to be on the streets, to straighten out situations.” He began studying criminal justice at Suffolk Community College, and was on his way to joining the New York Police Department when he hurt his back lifting heavy weights. He became a carpenter instead.

In another interview, Millie Alcamo sobbed on the telephone as she recalled hearing about McDonald’s death this week.

“It really set me back. I start thinking all over again about hearing the news,” said Alcamo, 31. Her husband, Joseph, a police officer in Far Rockaway, Queens, was killed in a car accident two years ago, while rushing to help a fellow cop in trouble. Nine months pregnant at the time, Alcamo opened the door of her Howard Beach, Queens, apartment at 3 that morning, and found a priest and two officers on the doorstep.

Two weeks later, she gave birth to her daughter, Stephanie, and gave her the middle name Jo, after a father she would never see. When asked what life has been like since, Alcamo said in a choked voice: “Horrible. Lonely, really lonely. I don’t really go out at all.”

For years, the widows of slain officers could not keep receiving their husbands’ pensions if they remarried. As a result of lobbying by the survivors’ group, the law was changed in 1991, reinstating the pensions of those survivors who had remarried.

“We’re a very strong bunch of women, because we’ve raised our children on our own,” said Grace Russell, president of the survivors’ organization. Russell’s husband, Michael, was playing a softball game in East New York with fellow officers from the 75th Precinct, when a dispute with local youths erupted. One of the teens fatally shot Michael Russell, and also killed another officer.

Although Russell’s group has not yet contacted McDonald’s widow, Police Department officials called on Russell Thursday to tap her experience. She said Janet McDonald “asked the Police Department, what is she going to tell her kids?”

For Russell, it was a chilling reminder of her own grim task 15 years ago, trying to explain to her 3-year-old daughter, Jessica, that her father was not coming back.

“She got up the next day and said, ‘Where’s Daddy?’ ” Russell said. “I sat her down on the stairs and said, ‘He was killed by bad guys.’ She yelled. She’s 18 now, and every once in a while we talk about that.”

Like Alcamo, Russell collected every newspaper article and photograph about her husband, pasting them into a scrapbook for her children, who were too young to remember their father. “It’s kind of morbid, but I knew they would want to know what happened,” she said. “At least they have something.”